CADBURY, DEBORAH

THE SCHOOL THAT ESCAPED THE NAZIS: THE TRUE STORY OF THE SCHOOLTEACHER WHO DEFIED HITLER (2022)

This story probably should have been told long ago for it calls attention to someone who must have been one of the more remarkable people of her time--Anna Essinger, born in 1879 into a nonobservant German Jewish family, who founded a coed children's boarding school in Germany in 1926 but who saw which way the winds were blowing by 1933 and spirited over 60 children out of Germany and into England, re-establishing her school there as Bunce Court. Having spent some time in the US, Essinger brought a strong Quaker flavor to the school. As time went on, the school continued accepting (Jewish) children from Germany but eventually included some English children as well. Many of the European children came from the Kindertransport, and after the war the school was accepting children who had managed to survive the concentration camps, who were of course far more severely traumatized than those admitted earlier.

The version of this book that I listened to included no notes or bibliography to support the children's stories of their experiences but there is no reason to doubt them for anyone with any familiarity with other Holocaust accounts. What those children endured is set forth here in detail and is tragic evidence of how much a human being can tolerate.

The transported children had no easy time of it in the school, either, for Essinger and her faculty had an uphill battle just keeping it afloat. There were difficulties in funding, and resources were so scarce that the school had to be largely self-sufficient, with the children assisting in growing food for the residents. The school's primarily Germanic composition, with the principal language being German and an emphasis on German culture, made it locally suspect as well, given the wartime atmosphere in England, where everything German was assumed to be Nazi--and the true genocidal horrors of the camps had not yet been exposed.

The school closed in 1948, and over the years Anna Essinger had cared for over 900 children.

This account was very informative--though of course quite harrowing.

8 December 2025

______________________________________

CALLAHAN, MAUREEN

AMERICAN PREDATOR: THE HUNT FOR THE MOST METICULOUS SERIAL KILLER OF THE 21ST CENTURY (2019)

This is the only time when I will have written a blog post about a book I haven't finished. But after reading about two-thirds of it, I feel qualified to make a couple of comments.

The serial killer, Israel Keyes, killed himself in prison. This account opens with his pursuit, capture, rape and murder of Samantha Koenig, an 18-year-old working alone in a coffee booth kiosk in Alaska. I stopped reading after his capture and interrogation by authorities.

The book isn't especially well written. There is some sloppiness in keeping track of the details, and there are some stylistic horrors, like the misuse of the verb "lay" and the grotesque new verb form, referencing, instances of which have been infesting the language lately.

I decided I didn't care enough about this particular psychopath's other crimes to read on.

By his own account, Israel Keyes sounds like as clear a specimen of a psychopath as anyone looking for one could find. The book's title, however, shows more thoughtlessness on the author's part. With the

21st century not even a quarter over, it is highly unlikely that there won't be other serial killers, quite possibly more horrendous ones than Keyes, by 2100.

Keyes's account under interrogation is so horrendous that the reader might be unable to take any more grisly details. Contemplating the vast number of young women who, eager for employment and needing to earn money, take jobs in situations like Samantha Koenig's that make them especially vulnerable, the reader might despair for the fate of the many young women in this very populous country who do not lead sheltered lives. Just who is looking out for them?

Another problem I had with this book concerns the intensely admiring tones with which one of the players in this drama is treated: Steve Rayburn, a Texas Ranger, assigned to the FBI case in Texas in pursuit of the killer. Whenever Rayburn figures in the account, he is described with an aura of something approaching glorification.

In an era where organizations like the "Proud Boys" seem to have inordinate powers (and lots of weapons, let's not forget), the Texas Rangers look alarmingly like another instance when people are inspired to take the law into their own hands and--all too often--make up the law as they go along.

4 November 2020

_________________________________

CAMPBELL, BEBE MOORE

SINGING IN THE COMEBACK CHOIR (1998)

This book was a bestseller, and I have a hunch that the author was aiming at the bestseller list as she wrote it. It has all of the earmarks of a book written with sales in mind--and of course a movie version.

Who can blame a writer for trying hard for sales?

I liked the book. It offers an unflaggingly interesting story, told in a lively way with witty dialogue. Maxine is a woman in her thirties, married to Satchel, a lawyer. Both African-Americans living in Los Angeles, where Maxine is the executive producer of a successful TV show resembling "Donahue."

Maxine, pregnant with their first child, makes a couple of trips back to Philadelphia, where the grandmother who raised her still lives. Lindy Walker, the grandmother, was a well-known singer but she has had a stroke and appears to be descending into depression and alcoholism.

Maxine tries hard not to meddle in her grandmother's life but she is drawn into the specifics of it, renewing old connections in her former neighborhood and pulling together the strands that will enable Lindy to stage a comeback.

Meanwhile, the pressures of her job are mounting, and eventually she has to face the failure of the show--but everything turns out beautifully because she's having a baby anyway.

The standard social-work line is overdone in this book. If Bebe Moore Campbell had done less analyzing and limited herself to telling a good story, the story would have been much better. She has an excellent command of contemporary conversational language. If only she could have let the characters speak without providing commentary.

19 February 2010

YOUR BLUES AIN'T LIKE MINE (1992)

The world needed Bebe Moore Campbell, who died a few years ago at the age of 56. I read her memoir, Sweet Summer: Growing Up With and Without My Dad, a while back--a very absorbing account and well told.

This novel, which takes place in Mississippi and Chicago, begins with the murder of a black teenager, Armstrong Todd, by a white man (abetted by his father and brother) seeking to avenge an imagined bit of flirtation between Armstrong and the white man's wife, Lily.

This part of the story sounds like the Emmett Till case but I don't know if the author had it in mind. It doesn't matter, for it is the kind of incident that was all too common in the south for centuries.

It is Armstrong's untimely death that shapes the lives of many of the other people in the novel, and we follow them into early old age. Armstrong's mother and grandmother, his father, and then there are the whites, whose lives are shown running parallel to those of the segregated black people in the story--Lily and her husband and his brother.

The author has not written a diatribe against white people though she very easily might have. She has understood the white people in her story. She has the rare gift of seeing why her enemies might be the way they are and of explaining them to us.

Along the way she gives us glimpses into routine examples of what it was like to live in a segregated world--the missed medical care, the missed education, the closed doors that black people faced every day of their lives and still face all too often in the US.

Bebe Moore Campbell has beautifully written a story that enhances the reader's perception of the way people have been--and still are--in the real world.

12 December 2009

__________________________

CAMPBELL, DENELE PITTS

NOTES OF A PIANO TUNER (1997)

Brief collection of pleasant reminiscences by a woman who became a piano tuner after having learned piano-tuning from her father. She tells of her experiences tuning pianos in homes and churches in the Ozark Mountains. She writes well and has something interesting and amusing to say--far more than can be said of many published writers.

21 February 2005

_________________________

CAMUS, ALBERT

THE FIRST MAN (1995)

This beginning of an autobiographical novel was published more than 30 years after the author's untimely death. Camus's daughter explains in an introductory note that the family hesitated to publish such a raw and clearly unfinished work earlier because the climate of opinion at the time of her father's death was hostile in spite of his Nobel Prize. The family felt that the imperfections in this fragmentary start of a novel would be glaring enough to make unfavorable criticism only too easy.

However, eventually the decision was made to publish it as it was, complete with the author's marginal notes to himself.

It is a fascinating and often beautiful work, fragmentary though it is. Camus has chosen to write an autobiography casting himself in the third person, possibly in order to gain objectivity as he wrote. In the story he is Jacques, a boy whose father died in World War I and who lives with his nearly illiterate and severely hearing-impaired mother and his grandmother (his mother's mother) in Algeria.

The family is not just poor but abjectly poor. But Jacques comes under the influence of a remarkable schoolmaster who arranges for him to go to the lycée on a scholarship.

At 13 he is put to work at a paying summer job because his grandmother believes he should contribute to the family income. He has to lie about his age even to get a job. A showdown comes after he has had to mislead his employer into thinking he will be a permanent employee when he himself knows very well he will be returning to the lycée. At the end of the summer he finds he can't follow his grandmother's advice and just walk off without returning. His employer learns that he has lied but takes pity on him and at least sends him packing with his final paycheck, which he might have kept.

The part of the novel that exists centers around Jacques's experiences in the poverty of Algeria--and around his developing courage in standing up to the stern grandmother who has beaten him regularly. The schoolmaster has beaten him too, but it is the grandmother's power that is the more formidable.

The writing is extraordinarily self-revelatory for Camus, who normally writes very restrained prose in his fiction. The style is so different from his other writing that one is tempted to wonder if he might have been experimenting with using James Joyce or Faulkner as a model. Or maybe his intention was to let all of the experience escape on the page and later to tighten up the writing.

The most remarkable passages are those dealing with the Algerian setting. He makes it come alive, much as he did so memorably in The Plague, set in the town of Oran.

His was not a religious childhood although he went through the first communion ritual--but only because it was just what one did at that time and in that community. His family paid no attention to masses, rosaries, or priests and never prayed. They were too busy trying to survive to have much energy or time left over for anything else.

This start of a novel provides fascinating glimpses into the mind of one of the greatest writers of the 20th century, a man who spoke out repeatedly against tyranny and totalitarianism in its many manifestations.

16 June 2011

_________________________

ČAPEK, KAREL

WAR WITH THE NEWTS (1936)

An amazingly prescient novel, a work of fantasy that envisages an increasingly powerful group of newts who have been trained by humans to talk. Slaves may be the obvious analogue to the newts, but the story is not so simple as that. While it is at it, the novel takes ironic pokes at Americans, racism, and nationalism, while maintaining its very strongly pro-Czech stance.

Written only two years before the author's untimely death, and during the ominous rise of Nazism in Germany, this book is grim and all too perceptive about humanity.

1 December 2005

__________________________

CARROLL, DAVID L. & DORMAN, JON DUDLEY, MD.

LIVING WELL WITH MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS: A GUIDE FOR PATIENT, CAREGIVER, AND FAMILY (1993)

Reading this book in 2009 is a strange experience. The "disease-modifying drugs" appear to have been unknown in 1993, when this book came out, for they aren't mentioned here. Also, MRIs were still new at the time.

So the book is badly in need of updating, but it is full of practical common-sense advice and is particularly good as a resource on exercises.

28 June 2009

___________________________

CATHER, WILLA

MY ÁNTONIA (1926)

It has probably been close to 50 years since I read this book, regarded as Willa Cather's best novel and still likely to turn up on recommended reading lists in schools throughout the land.

--Maybe not though. It does contain a couple of disturbing passages that perpetuate racist stereotypes but perhaps an understanding, forgiving reader can pass over them by telling herself that this was "the way people thought" in Cather's day (the book's first edition came out in 1918). Still, her use of the word "pickaninny," with even a suggestion that African-American have smaller brains than white people, are hard to overlook. The entire literary canon probably may need to be scrubbed of its racial and ethnic prejudice.

And yet here Cather gives us a story that looks like an attempt at broadening the horizons of her readers by presenting us with a Bohemian (Czech) family in Nebraska, with the focus on Ántonia, who gradually develops into someone resembling an earth mother, clearly very much admired by the narrator, her childhood friend, Jim Burden. There is this passage, near the end of the story, where he sums up his impressions of her and universalizes her:

She lent herself to immemorial human attitudes which we recognize by instinct as universal and true. I had not been mistaken. She was a battered woman now, not a lovely girl; but she still had that something which fires the imagination, could still stop one’s breath for a moment by a look or gesture that somehow revealed the meaning in common things. She had only to stand in the orchard, to put her hand on a little crab tree and look up at the apples, to make you feel the goodness of planting and tending and harvesting at last. All the strong things of her heart came out in her body, that had been so tireless in serving generous emotions.

It was no wonder that her sons stood tall and straight. She was a rich mine of life, like the founders of early races.

Throughout the story it probably occurs to the reader that Jim should marry Ántonia. Why he doesn't is never stated. But if he had married her, the whole panoramic scene of Ántonia surrounded by her husband and some 10 or more children, all speaking Czech as well as English, would not have been possible, and the chances are that she could not have been quite as dramatic an "earth mother" figure with that scenario.

But within the framework of the story, what reasons could there be for Jim's failure to court and win the woman he clearly loves?

At one point he has to make a choice: whether to go East to continue his studies in college with his mentor, a man he admires. He opts to go East. He becomes a lawyer. Some 20 years later, he returns to Nebraska and sees Ántonia again.

Not to make too fine a point of it, but it looks as if Cather is implying that the class differences between Jim and Ántonia would have been insurmountable--she of foreign-born farming people, he from a more settled, less-recently-arrived lineage. He could move away from farm life. She couldn't. He could get a job where his mind was valued and where he no longer had to do heavy physical work night and day. She couldn't escape--nor is there any indication that she would have wanted to.

What we're left with, then, is the settled world that many were lulled into feeling was well established and comfortable. It is, disappointingly, a well written book that rests on a sandy foundation, but it is the same sandy foundation that underlies many books that sell well.

August 18, 2019

SAPPHIRA AND THE SLAVE GIRL (1940)

Short novel about a Virginia family in 1856, with Sapphira, the mistress of the household, turning against her favorite slave girl, Nancy. Nancy, in danger of being raped by a visiting nephew of her master’s, manages to escape to Canada by the Underground Railroad with the help of Sapphira’s daughter Rachel Blake.

This was a good book, though it almost seems as if Cather might have lost interest in it when only half done, for its epilogue seems tacked on as an afterthought, meant perhaps just to put an ending to the story..

9 March 2002

________________________

CEP, CASEY

FURIOUS HOURS: MURDER, FRAUD, AND THE LAST TRIAL OF

HARPER LEE (2018)

The first half of this account concerns the long and complex history of the career of the Reverend Willie Maxwell, an African-American preacher who took out insurance policies on several relatives who then died under suspicious circumstances. Then Maxwell was shot at a funeral he was conducting. Curiously, the lawyer who had defended Maxwell several times also defended his killer. Maxwell was never convicted of any of the suspected murders but the evidence against him was persuasive.

Harper Lee, by then the highly successful author of To Kill a Mockingbird, who had an abiding interest in legal cases, attended the trial of Maxwell's killer with the intention of writing a book about it--possibly a book somewhat like Truman Capote's In Cold Blood. But that was in 1978, and she lived until 2016 but apparently set the project aside and never returned to it.

The author focuses on the lifelong friendship of Lee and Capote and reveals the extent to which Lee was involved in the making of Capote's "nonfiction novel," In Cold Blood. Lee was his research assistant, traveling with him to Nebraska and serving as an intermediary of sorts between Capote, who wanted information from the reluctant Nebraskans who shied away from someone as foreign to their milieu as Truman Capote evidently was but who felt they could open up to Harper Lee. She compiled and organized vast amounts of information for the book.

Interestingly, there has been some evidence that Capote may have helped her in the writing of the first part of To Kill a Mockingbird.

This is an absorbing account--though its main audience will probably be readers of Harper Lee--who turned out to be only a "one-book author," sadly.

19 May 2022

________________________

CHEEVER, JOHN

BULLET PARK (1969)

I found this novel to be a slog. There's a character named Nailles, and then there's a character named Hammer. The story becomes increasingly bizarre as time goes on.

I can't say much to recommend it though there are some witty passages.

24 June 2013

_________________________________

CHEEVER, SUSAN

NOTE FOUND IN A BOTTLE: MY LIFE AS A DRINKER (1999)

Here we have the life story of the daughter of writer John Cheever, exploring her family’s struggle with alcoholism and refusal to face it. This is a very privileged woman’s history but honestly told.

23 July 2001

________________________

CHERNIN, KIM

THE OBSESSION: REFLECTIONS ON THE TYRANNY OF SLENDERNESS (1981)

This is a very thorough and thoughtful exploration of the modern woman's obsession with being thin, an obsession that has shown no sign of waning over the decades since this book appeared.

The author has mined the psychological literature, especially material in the Freudian camp, but she isn't just parroting psychoanalytic theory here. Her idea is that women inherently have so much power--to conceive, bear, and nourish children--that we inspire fear, and with fear often comes a wish to stifle us, to keep us subservient.

She has very little explanation for how the world got this way but offers many persuasive examples to show that it is this way. It is not her objective to go into the historical and economic developments that helped this situation to come into being. Rather, she is interested in persuading us that the emphasis on being thin is dangerous, manipulative, controlling, and very unfair--and ought to come to an end.

She gives special attention to anorexia nervosa, and this is one place where an updated version of this book would be very helpful, for considerable work has been done on investigating eating disorders in recent years.

2 May 2010

_____________________________

CHESNUT, MARY BOYKIN

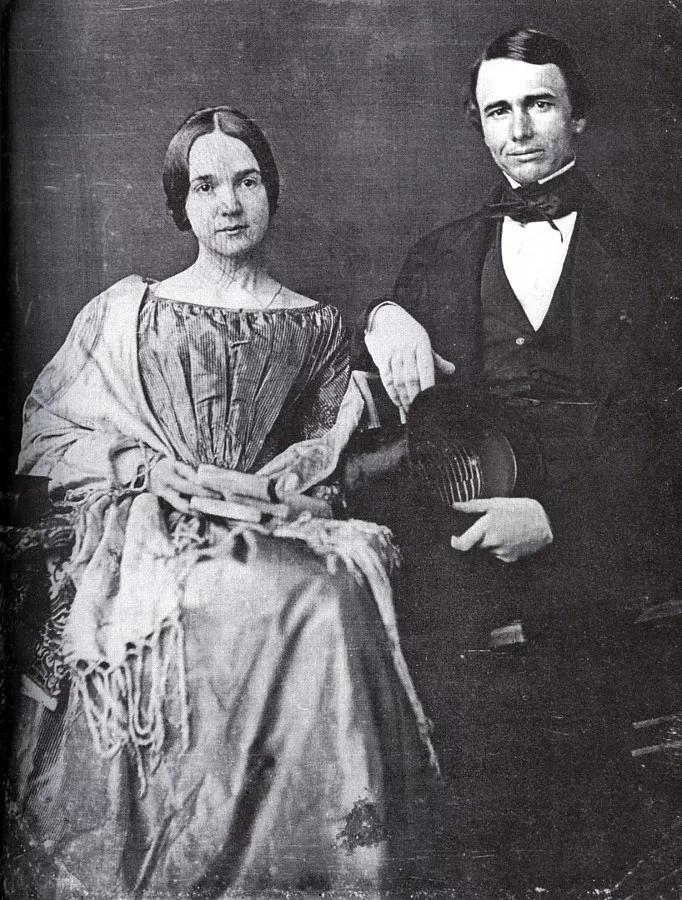

MARY BOYKIN CHESNUT'S CIVIL WAR (1981; 892 pp.)

Mary Boykin Chesnut (1823-1886) kept a diary during the Civil War even though she was being considerably affected by it. Her husband was a brigadier general in the Confederate military, and the couple were good friends of Jefferson Davis and his family. The Chesnuts were childless, and Mary often suffered from bouts of ill health, but she knew an astonishing number of people and interacted with them often.

She apparently revised her diary in later years but it wasn't published until after her death. In 1905 a first version of it appeared, with another in 1949, and now there is the splendidly annotated version by the eminent historian, C. Vann Woodward--liberally supplied with explanatory footnotes.

Early in the course of the war, she makes it clear that she knows slavery is wrong and she is sure that it is doing to end. Her attitude toward the slaves is harder to determine simply because when she makes a statement, it's not always clear if she is quoting someone else or giving her own views. This may have been a problem with her original diary as well.

By war's end she notes that their own former slaves (a thousand of them) are preferring to stay on the premises even though they are now free--though she also cites one of them who gave the astute observation that they had nothing to go to anywhere else. Chesnut is quite aware that the idea of "40 acres and a mule" was apt to be unreal--and that, even if real, it would not be nearly enough to survive on beyond mere subsistence.

(Which was what I saw as a child in the South in the 1940s-1950s, many decades after the war: mile after mile of weatherbeaten shacks without indoor plumbing or much if any electricity, with emaciated, haggard people laboring in cotton fields for long hours, with children getting almost no schooling.)

Mary Chesnut's wit and keen observation make this diary, however confusing and flawed it may be, immensely valuable for its insight into what the war was actually like. She was not entirely sheltered from the war although she relied heavily on the help of the "servants," as well as on family and friends--and for this part of her life she would have had access to many resources. Money was never a problem for Mary Chesnut and her circle--until the war's end, when situations often changed abruptly and catastrophically.

She seems to have a thorough command of the important developments as the war proceeds. The diary is full of commentary on battles and their outcomes, and she helps by bringing provisions to wounded soldiers.

She often remarks on the seemingly unaffected demeanor manifested by the slaves--a composure that was surely carefully cultivated as a front they felt obliged to maintain, out of fear of reprisals from the harsh system in which they found themselves. Even though Chesnut's account shows that their slaves were treated quite benevolently, the system was still slavery, and the enslaved people were surely aware of that fact.

During the firing of Fort Sumter, for instance, Chesnut writes of the constant noise of the war, and of how the "servants" keep on bringing trays of food to her and the others in the household:

You could not tell that they hear even the awful row that is going on in the bay though it is dinning in their ears night and day, and people talk before them as if they were chairs and tables, and they make no sign.

Mary Chesnut's views throughout are a woman's perspective on the war and slavery--the views of a highly privileged white woman, to be sure, but one who has done some reflecting, as when (in 1863) she declares that there can be no such thing as a Christian soldier as there is nothing Christian about war.

The diary ends just after the end of the war, but Mary Chesnut went on living for a couple of decades, during which her husband died and the remaining property went to a male heir. Mary Chesnut, who came from a prosperous family and married into another prosperous family at 17, died in poverty.

She had known a way of life that was fundamentally defective and fragile, and at times she seems aware that the "aristocracy" established by the Southern plantation owners is doomed, even while she herself has had a very active part in maintaining it.

Some passages in her account sound as if the Southern plantation culture was an attempt at duplicating the British aristocracy. To be sure, there were no earls or dukes but there were certainly colonels, real or self-appointed, throughout the South. On this strongly militaristic scaffolding was built an entire cult of "gracious living": the splendidly attired ladies and gentlemen, the thoroughbred horses, the wining and dining and elaborate social events, the private schools, the expectation that some people would always be in charge of the churches, colleges, and banks while others--often regarded as not quite human in spite of overwhelming evidence contradicting this absurdity--would be keeping themselves obediently in the background and making themselves useful.

The rice, the tobacco, and the cotton kept being produced somehow, and the money kept rolling in. It supported the Southern lifestyle.

Mary Chesnut saw the end coming. Clear-eyed through the war, she witnessed the tragic carnage and was no stranger to tragedy and pain. She tried to tell the truth, and we can be glad she kept that diary.

8 August 2024

______________________________________

CHILDERS, THOMAS

THE SHADOWS OF WAR: AN AMERICAN PILOT'S ODYSSEY THROUGH OCCUPIED FRANCE AND IN THE CAMPS OF NAZI GERMANY (2002)

The author of this account of Roy Allen's World War 2 experiences after his plane was shot down is a professor of history who has written other books about Nazi Germany. Roy Allen, as the pilot, was the last crew member to parachute out of the plane, and he lost track of the rest of the crew for quite a while. He found shelter with a French family who were sympathetic to the Resistance at a time when France was overrun with Germans and opposing the occupying Nazis was very dangerous.

Eventually Roy was caught in his attempt to escape from France and return to his unit--and he was sent to Buchenwald, where he languished near death for many months, although he should have been in a camp for military prisoners of war. His situation improved only as the war was ending.

This is a moving account, containing highly detailed descriptions of everyday life at Buchenwald. I have read other accounts of concentration camp life, but this one offers a closeup look at the routines and the horrors of the prisoners' unimaginably nightmarish existence there.

3 February 2007

________________________

CHOPIN, KATE

"THE AWAKENING" AND SELECTED STORIES (1899)

The author was a turn-of-century writer, and she has recently become the darling of the feminists. Her writing contains much Southern bigotry.

9 August 1998

________________________

CHURCHWELL, SARAH

CARELESS PEOPLE: MURDER, MAYHEM, AND THE INVENTION OF THE GREAT GATSBY (2014)

The facts about F. Scott Fitzgerald's life are well known and have been explored in minute detail by a vast industry of literary researchers. That the territory has been so thoroughly mined may be one reason why this author felt obliged to present her study almost as if it were in the form of Webpages, with little snippets of text, very short chapters interspersed with illustrations and quotations. The result is a book that seems aimed at a large audience.

She may also have felt obliged to come up with a somewhat original idea, and so her book is constructed around three stories, tied together loosely by her impressionistic attempts at finding connections: the life of F. Scott Fitzgerald and Zelda, the story told in The Great Gatsby, and a news story involving a murder--the Hall-Mills murder--that was capturing the public's attention in 1922 and for some time afterwards.

Churchwell sees some parallels between the known facts about the murder and the deaths that occur in Gatsby. Whether she has a good case is debatable, but en route she treats us to many anecdotes about the alcohol-saturated world in which this author lived.

She clearly respects Fitzgerald's talent and in my opinion attributes far more depth to his writing than is warranted. Her account is fanciful at times, drawing on the half-baked but over-worked romanticism that seems to have pervaded much of Fitzgerald's fiction.

She has to reach pretty far afield to make her idea work, too--as when she notes a similarity between the names Jay Gatsby and Jane Gibson (the notorious "pig woman" of the Hall-Mills case).

2 February 2019

__________________________

CLEMENS, SAMUEL L. [MARK TWAIN]

A MURDER, A MYSTERY, AND A MARRIAGE (1876; published 2003)

This very brief narrative was written as a skeleton plot for a writing contest Mark Twain envisaged as a way of attracting readers to his friend William Dean Howells's magazine, The Atlantic Monthly. Twain would provide the skeleton plot, and other invited established writers--including the unlikely Henry James--would supply their own stories based on the skeleton plot. Nobody ever submitted an entry, and the project died--with Twain's story lying unpublished until 2003.

It has appeared now with excellent commentary by Roy Blount, Jr., who fills us in on a number of relevant details about Twain's life and attitudes.

The story itself is slight and somewhat corny, but it was meant only as a skeleton plot. For reasons that are obscure, Twain used the occasion to poke fun at Jules Verne's novels--and this segment of the brief narrative is hilarious.

8 August 2009

LETTERS FROM THE EARTH (1939; 1962)

These posthumously appearing essays and fragments underwent drastic restoration in the 1962 version. By this time Clara Clemens, the author's daughter, had given permission to publish an unexpurgated edition. Here we presumably have the "real" Mark Twain, bitterly cynical and opposed to organized religion.

10 February 2006

________________________

CLINTON, HILLARY RODHAM

(CO-AUTHOR: LOUISE PENNY)

STATE OF TERROR (2021)

People active in the political sphere have been known to write novels. Benjamin Disraeli comes to mind. Now a former US Secretary of State and former Presidential candidate has written--with Louise Penny as co-author--an espionage thriller. At its center is Ellen Adams, a US Secretary of State.

The plot thickens and then thickens some more. I'm not a reader of espionage thrillers and am too unfamiliar with the genre to know whether this is a good instance of it. Like most espionage narratives, though, it soon became almost too complicated to follow, and the white hats kept being revealed as really black hats, and vice versa.

Hints of sinister conspiracy abound, and there are incidents involving bombs, al Qaeda, and cellphones. But most spy tales leave me feeling as if I'm mired in quicksand.

13 December 2022

WHAT HAPPENED (2017)

This book by the candidate who lost the U. S. 2016 Presidential election almost had to be written. Hillary Rodham Clinton could have subsided into the background and played the good sport after being defeated by Donald Trump for an office she was clearly well qualified for. But her supporters were owed an explanation, and here it is.

Of course someone who has been on the political scene--and right near the top much of the time, as the wife of a two-term President and later as Secretary of State--for such a long period isn't going to take being defeated by an unscrupulous bigoted entrepreneur lightly. She offers several explanations for the election outcome and is gracious in acknowledging that she made some very stupid mistakes during the campaign.

But she has some serious complaints about the way the U.S. system now works. She sees it as broken and corrupt, easily controlled by moneyed interests. She calls for people to step up to the plate and start doing something to quell the rising tide of racism and xenophobia in this country.

Much of her book is political boilerplate. Peace? She's for it. "Tolerance--basic standards of decency"? Check. She's leaning over backwards to be ecumenical, too. In the chapter entitled "Love and Kindness," after admiring Pope Francis's TED talk where he called for a "revolution of tenderness"--a phrase she loves though I'm not sure what it means--she comes up with "radical empathy" as a name for what we need in the U.S. Though both phrases have a certain novelty, their meaning eludes me. And a little later a quotation from Pope John XXIII pops up.

She sees herself as having broken new ground, as having made history, by being the first woman to be nominated and nearly elected to the Presidency of the U.S. In this book she may be setting out to show that a woman like herself would have been a more empathetic leader than Donald Trump--or perhaps than any male candidate. She often emphasizes her religious faith (Methodism) and presents herself as someone who is always thinking of others--picking up gifts for people who have had babies or got married, hugging people. Surely a man campaigning to be elected President wouldn't be mentioning such gestures in a book about that campaign even if he had thought of them.

Like many women of her generation, she may be too eager to present herself to the world as surrounded by a perfect family. She praises her daughter Chelsea to the skies, almost to the point where it looks as if Chelsea is being put forward as a player on the political scene--even though Chelsea is rumored to be close friends with Ivanka Trump Kushner, the current President's daughter--a connection that Hillary Clinton's book leaves unmentioned.

However, she highlights her contention that there has been a concerted effort at voter suppression--disenfranchising U.S. voters on dubious grounds--and that the 2016 election results may have been skewed by the involvement of Russia.

One of her reasons for maintaining that Russia might have meddled in the U.S. election is that she is fairly certain that Vladimir Putin dislikes her intensely and wanted to make sure she didn't win. At first this looks as if she might be imagining a vendetta that isn't there but she makes a strong argument for it. She also points to the extensive financial ties between Trump and the Russians in support of her claim that the Russians interfered with the 2016 election.

This is a book that avoids self-pity but manages to make a strong case in favor of a woman who probably should have been the U. S. President.

2 June 2018

________________________

COHEN, RANDY

THE GOOD, THE BAD, AND THE DIFFERENCE: HOW TO TELL RIGHT FROM WRONG IN EVERYDAY SITUATIONS (2002)

For some years I'd been aware of a syndicated newspaper column about ethics, and I glanced at it enough times to be interested in this book, which is mainly a collection of some of his columns. The column as it ran in The New York Times was called "The Ethicist."

Although the author has no particular training in ethics or philosophy, his down-to-earth advice and ability to articulate his views clearly seem to have won him an audience. He has spent a large part of his life as a writer for various TV shows, and the Times discontinued his column when he donated to MoveOn.org, evidently because he was unaware that the paper had recently adopted a policy prohibiting its writers from contributing to activist organizations.

This background information comes from Wikipedia, however, and may be open to question.

Readers write in with their ethical problems, and he replies. Sometimes there are follow-ups and responses from other readers. Occasionally there is a guest columnist replying. It is particularly refreshing when a pundit of this sort is willing to reassess his opinion and admit he was wrong, and Randy Cohen does so several times in this short book.

Ethical questions can often be murky, and one problem with the book is that sometimes the readers' descriptions of their problems lack detail. One needs to know more about the situation before replying, I should think.

But the book is witty and amusing, and I usually agreed with his opinions.

21 February 2012

_________________________________

COHEN, RICHARD M.

BLINDSIDED: LIFTING A LIFE ABOVE ILLNESS: A RELUCTANT MEMOIR (2004)

The author, who happens to be married to Meredith Vieira, the TV news broadcaster and talk-show host, was also in the TV news business until multiple sclerosis and other disorders entered his life. He tells his story, with considerable discussion about the impact of his illness on his wife and three children. After the MS diagnosis, he was found to have colon cancer, which returned later. The surgeries and their complications, and the pain of the colon cancer, made their family life difficult, but Richard Cohen takes a wryly humorous view of himself and freely owns up to his mistakes.

His father is a doctor who also has MS, and his grandmother had MS as well (although she apparently never realized it).

This is a well-told and honest account of coming to terms with chronic illness.

7 January 2008

CHASING HOPE: A PATIENT'S DEEP DIVE INTO STEM CELLS, FAITH AND THE FUTURE (2018)

This interesting account isn't simply a rehash of the author's previous book (see above). Here we have his report on his venture into the promising new world of stem cell treatments for MS--a venture for which he has to have been more courageous than many of us would be, for the treatment's benefits are still debatable.

Along the way, he is concerned about hope. Can one have hope without faith? He interviews assorted people, such as Rabbi Kushner (author of When Bad Things Happen to Good People) and TV anchor Tom Brokaw, struggling with multiple myeloma.

His enthusiasm for stem cells began when he and his family attended a conference on stem cells at the Vatican. Soon he was in the hands of Dr. Saud Sadiq of the Tisch MS Research Center in New York, and he has clearly become a disciple of Dr. Sadiq, whose name is well known in MS research.

The treatment he received, which he describes in some detail, was part of a Phase I clinical trial involving some 20 patients. He does not say so in so many words but the results may have been disappointing, for he acknowledges that the improvement he noticed was only modest and may have been temporary. There was a 2-year follow-up of that clinical trial that makes it sound as if stem cell treatment may not deliver very encouraging results:

The author has done a great service for everyone with MS by his willingness to undergo this experimental procedure and by his clear presentation of the account of that experience.

27 April 2021

_____________________

CONRAD, JOSEPH

THE SECRET AGENT: A SIMPLE TALE (1907)

Returning to this novel after several decades, I am struck by its depth. Although there is a veneer of something approaching sensationalism and even sentimentality at times--very unlike Conrad's other works--he is saying something important, something that even more than a century later rings appallingly true.

Set mainly in a grimy, seedy London, the story brings in several characters with a foreign background: Verloc, the secret agent, who travels to France often; his associate Comrade Ossipon and his apparent handler Mr. Vladimir, both strongly suggesting Eastern Europe. There are also Verloc's associates Karl Yundt and Michaelis the ticket-of-leave man, both of indeterminate origin.

Verloc keeps a store dealing in risqué reading matter as well as (probably) revolutionary tracts. This is his means of earning a living to support his wife Winnie as well as her mentally handicapped brother Stevie, who is still a boy. Verloc has long been a secret agent for an embassy but Mr. Vladimir makes it clear to him that he is in danger of having outlived his usefulness--unless he can do something dangerous, something attention-getting, to shake up the powers that be.

Coming out in 1907, this book would have been written at a time when anarchy was in the air throughout Europe. Conrad shows us the sordid and warped world in which his anarchists live, but it is mainly their ideology and their methods that are the focus of his attention.

That they are unscrupulous and ruthless men goes without saying. We see it in Vladimir, we see it in Ossipon, and especially (at the end) we see it in the Professor, who enunciates ideas that are clearly fascistic. The Professor would like to see all of the weaker people on earth exterminated--while assuming that he himself would not be among those who must go.

While the scenes are often bleak and even gory, there is never a hint that the supernatural is at work. Religion goes unmentioned; no representatives of the clergy are on the scene. This is a completely secular, dog-eat-dog world. Conrad gives the entire story an ambience of anonymity and impersonal bureaucracy proleptic of Orwell's 1984 by often referring to most of the characters by their occupational titles instead of their names. The exceptions are Verloc, Winnie, and Stevie, who are clearly meant to be not nearly as dedicated to an ideology or to any one occupation as the others--whether anarchists or representatives of the established order.

The higher up someone is in the hierarchy, the less likely they are to be named. There is Chief Inspector Heat of the police, but his superior is called the Assistant Commissioner, and Sir Ethelred, the "great personage" whom he consults, is referred to only rarely by his name, which is always Sir Ethelred.

Conrad comes perilously close to the sentimental in his characterization of Stevie, who feels an intense compassion for any suffering creature. At times Stevie is a bit too much the little child who shall lead others to the light, as in an exchange with his older sister Winnie. Stevie asks what the police are for, and Winnie replies: "'Don't you know what the police are for, Stevie? They are there so as them as have nothing shouldn't take anything away from them who have.'"

Stevie says: "'Not even if they were hungry, mustn't they?'" and Winnie replies, "'Not if they were ever so!'"--going on to point out, "'You aren't ever hungry.'"

The reader is clearly meant to side with Stevie in this discussion, but perhaps the point is made too emphatically when Stevie shows a fascination with the concept of "poor" (probably meaning "pitiable" more than "indigent" here) and sums up his view with the remark: "'Bad world for poor people!'"

Stevie's fate, once it becomes clear to the reader, is horrendous. By an accident--he stumbled apparently--the explosive device didn't reach its intended target.

Winnie's subsequent decline into near-madness and suicidal despair is described realistically and very affectingly, and the final scenes involving Comrade Ossipon, who we know to be cruelly exploiting her, are about as grim as such scenes can get. Winnie, raised at a time when even poorer women in England would have been somewhat sheltered and taught to rely on men for support, believes that she can trust Comrade Ossipon. She has cared about her mother and brother and about Verloc.

Interestingly, at the very end of the story the attention shifts briefly to one of the anarchists who has been largely in the background up till now--the Professor. His terrifying philosophy, based on some of the theories of eugenics that were popular at the time, is articulated, and the final sentence describes him walking along. After we have learned that the more humane characters in the tale are now all dead, we see that this proponent of a cruel ideology has survived:

He passed on unsuspected and deadly, like a pest in the street full of men.

30 August 2016

THE END OF THE TETHER (1902)

An aging captain, who had gained some distinction previously with his maritime achievements, has lost most of his money in a business transaction that failed and is now widowed with one daughter, who lives in Australia, married and with children. He’s devoted to the daughter and disturbed to learn that her husband has become an invalid, useless as a support for the family, and she is having to run a boarding house to support them, including the invalid husband. The captain takes on a three-year-job as skipper of a vessel, a job no one else wants because the owner is also the craft’s engineer and is a bitter, paranoid, hostile person. The captain puts his remaining funds into a part-ownership of this vessel on condition that after three years he can leave and withdraw the full amount, which he counts on doing—so he can give it, intact, to his daughter to help her. But it develops, on nearly the last run of this steamer, that the captain is losing his sight and has been doing so for quite a while without telling anyone—not wanting to upset his daughter and afraid of losing his job on the steamer. He keeps on concealing his disability, but one or two envious men on board have figured it out, and one—the owner—is convinced that Captain Whalley is lying when he says he has no more money. The owner bought the vessel by winning a lottery, and ever since he has been obsessed with playing the lottery, hoping to win again. His greed is frightening. He plots to throw the steamer off its course and deliberately wreck his own vessel so as to collect insurance money.

This novella is affecting, with its story of Whalley’s tragic death. The captain is noble in his rather simple determination to be of use to his child, even to the extent of concealing a serious physical impairment so as to spare his daughter the worry—and to safeguard the only employment he has that will enable him to help her.

10 January 1995

THE NIGGER OF THE "NARCISSUS": A TALE OF THE SEA (1897)

James Wait, the man on board the “Narcissus” who holes up, allegedly too ill to work for most of the voyage, astonished me by the way he subjugates most of the men, playing on their pity and fear in order to get them to serve him. Even more surprising was his accomplishing this in spite of being black and therefore contemptible in the opinion of most of the others.

The author of the preface supposes that the story’s theme is the demoralization of the men by James Wait and his illness (or “illness”). Towards the end of the voyage he is accused of malingering, which he admits, but it is soon obvious that he actually does have TB. Eventually he dies, but not before at least one of the men has had the bright idea of trying to take advantage of his vulnerability by robbing him, and not before the idea has become current that a dying man on board is bad luck and has caused the ship to be becalmed. I fail to see that the men are demoralized at all. The final judgment on them (by the narrator) is that they were a good lot.

At first I thought that the story would concern the resentment of a closed community whose labor is needed for its own survival when one of its number is or pretends to be unable to work, but this is only a secondary motif. In fact, in spite of the occasional murmurings of resentment to the effect that the others were having to do extra work on account of the disabled man, who would still collect his pay while doing nothing, but the others would get no extra pay for their extra contributions, the ultimate result of the severely strained voyage seems to be that they all come through it unscathed. So even on board ship, where the number of hands needed for a given voyage has to be very carefully calculated, the group can endure the incapacity of one of its number and even the laziness of numbers of others without any harm and can even find the time and resources to shower the disabled man with sympathy, visits, and gifts, even though James Wait is unlikable and imperious in the extreme.

It is the possibility that he might not live to set foot on land that inspires the crew to so much compassion, and indeed he does not live.

25 March 1986

_____________________________________________

COOPER, CANDY J.

SHACKLED: A TALE OF WRONGED KIDS, ROGUE JUDGES, AND A TOWN THAT LOOKED AWAY (2024)

The author, a reporter, gives a clear account of the "Kids for Cash" scandal innvolving a couple of judges in the Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania, area who hustled thousands of juveniles through the court system and into harsh detention facilities for minor offenses. Many of the children involved were promising students whose lives were severely impaired by the experience. It turned out that the judges had been accepting money from a private prison in exchange for these harsh judgments, which resulted in higher occupancy for the prison. Judge Mark Ciavarella succeeded in these monstrous adjudications between 1996 and 2009.

4 October 2025

_________________________

COUPLAND, DOUGLAS

GENERATION X (1991)

Dag, Claire, and Andy are the three main characters--all in their twenties, with Dag the narrator. These young adults have parents who are apparently far from indigent or indifferent, but they feel alienated from their families. These people hold McJobs, and in their spare time (of which they have a great deal) they pop pills carelessly and indulge in pointless fantasies as if they might be undiscovered literary geniuses just waiting to happen. They have easy mobility--they travel around freely in planes and take cars as a given. They gloom, they sulk, they come up with vague but probably meaningful remarks.

This is Kerouac all over again, and I found Kerouac tiresome. Generation X seems to be accusing the older generation of having created a bleak world, but some members of the older generation may be horrified at the self-absorption they must have fostered in their offspring by letting that TV stay on so much of the time and by subscribing to the idea that one's children are the center of the universe. This is what those children have grown up to be--navel-gazers par excellence.

1992

_________________________

COURTIER, MARIE-ANNICK

COOKING WELL: MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS (2009)

This cookbook is part of a series called Cooking Well, with each cookbook intended for a specific disorder (osteoporosis is one). I haven't looked at any of the other books in the series and so don't know if some recipes are repeated in other volumes.

The Foreword is by Vincent F. Macaluso, MD, who is a neurologist specializing in MS who also has MS. Dr. Macaluso is also listed as being on the BiogenIdec National Faculty, and he takes Tysabri. The author's credentials are less clear, but she dedicates the book to two friends who have MS.

A paperback book of 150 pages for about $9.00--not a bad deal, you say? Maybe for some it will be a treasure, but I'm returning my copy for a refund.

I was hoping for some helpful recipes. I am glad that the nutrition information for each is included, but I'm not sure how accurate some of it is. A granola recipe calls for "muesli cereal" without specifying what kind--or even what ingredients go into the muesli--leading me to question the nutrition information for the granola because there are so many varieties of muesli out there, and many people use their own muesli recipes, which can differ widely in their calorie counts and other nutrition information.

The first 38 pages of the book are taken up by general advice and nutrition information--mostly of the standard sort that is widely available. I'd have welcomed more suggestions on how to open jars and bottles safely, how to avoid getting burned or over-exposed to kitchen heat, and how to do basic tasks with fumbling hands, dim eyesight, and general unsteadiness.

The recipes should please vegetarians as there are over 35 recipes that do not involve meat, poultry, or fish.

However, many people with MS don't have the money for the kinds of ingredients called for in these recipes--and often they don't have the means of visiting the places that sell some of the more obscure ones: anchovy fillets, cilantro, wild rice, Portobello mushrooms, almond meal, flaxseeds, ginger root, wild smoked salmon, Pecorino cheese.

Nor can it be assumed that someone with MS has a blender, a food processor, or a microwave oven, as many of these recipes assume.

The 6x9-inch format is a handy size, though I'd have preferred a spiral-bound book that could lie flat. Also, many bits of important information are set in black type against a fairly dark gray background, which is difficult to read.

Some of the recipes seem so slight that I wonder why they were included--except perhaps to bulk up the book. Cottage Cheese, Raisins, and Walnuts (1 serving) is an example. And there is no index--a big shortcoming, in my opinion. If you want to see if the book includes a recipe for chicken cacciatore, for instance, you can find out only by leafing through its pages.

And though the author knows the meaning of "brunoise," I had to look on the Internet to find out what it meant. It was in no print dictionary I own. I've read a few cookbooks over the years and never encountered this term, but I'm not a gourmet cook. It would have been nice if the book had included an alphabetical glossary of terms like brunoise and bouquet garni. Bouquet garni is defined in the thirty-five pages of informational text preceding the actual recipes, but it's hard to find. Every cookbook that uses the term seems to have a slightly different description of what a bouquet garni is.

Many of the recipes are for 4 servings and are usually simple enough for a mobility-impaired person to manage, given the right ingredients and equipment. And that's the problem.

All too often material about MS or for someone with MS seems to assume that the person with MS is fairly prosperous. It's time to put an end to that idea and recognize that this disorder isn't limited to people with high incomes. Unfortunately, this book doesn't serve the needs of everyone who might have MS, and that is a great shame.

3 July 2009

________________________________

COYLE, PATRICIA K., MD, and HALPER, JUNE

MEETING THE CHALLENGE OF PROGRESSIVE MULTIPLE SCLEROSIS (2001)

Since this book came out ten years ago, its information is often out of date. For instance, Rebif was not available in the US as a disease-modifying therapy for MS when this book appeared. And the authors' recommendations on PSAT and mammography testing are no longer current.

But the book is full of common-sense advice on the management of this chronic and disabling disorder.

17 July 2011

______________________________

CREWS, FREDERICK

THE MEMORY WARS (1995)

This book consists of some essays by Crews on Freudian theory in connection with the “repressed memory syndrome” that has enjoyed some popularity--and it includes several detailed rebuttals by eminences in the psychotherapy field. Crews is a tad vitriolic, but I thought his argument was persuasive—and one that desperately needs airing. It is time to debunk “repressed memory” theories.

Crews surveys the recent literature on repressed memory—the book is well supplied with references—and remarks that the seminal work, the one that sold extremely well and is often mentioned in other works, is the one by Ellen Bass and Laura Davis, The Courage to Heal (1988).

Crews maintains that this book has had an immense influence—and that one effect of its inflammatory and irresponsible theorizing has been to destroy family ties. Lawsuits have been filed against allegedly abusive parents 30 years after the “fact”—and some of these parents, usually innocent, are languishing in jail—all on the basis of “repressed memories” dredged up by their grown children.

The Memory Wars should be a much-needed corrective.

16 February 1998

_____________________________

CROMBIE, DEBORAH

A SHARE IN DEATH: A DUNCAN KINCAID AND GEMMA JAMES MYSTERY (1993)

A group of assorted people are assembled in a time-share, and among them Duncan Kincaid, a newly promoted detective superintendent at Scotland Yard, has been fortunate--or unfortunate--enough to find himself thanks to the generosity of a relative.

He soon finds himself embroiled in the murders of a couple of people there and must tread carefully for fear of ruffling the feathers of Detective Chief Inspector Nash, who resents the intrusion of someone from Scotland Yard.

There are quite a few suspects on the scene, and the real murderer of course turns out to be someone the reader hasn't been paying much attention to.

It's an engaging story, well told.

8 October 2018

______________________

CUMMINGS, BRUCE [BARBELLION, W. N. P., pseud.]

THE JOURNAL OF A DISAPPOINTED MAN (1919)

I read this book in 1980 but it was memorable. It is one of the earliest known accounts by someone with disseminated (multiple) sclerosis. The author, who was British, lived from 1889 to 1919. He tells of discovering that his brothers had concealed his diagnosis from him.

This is his actual diary although there is not much detail about his symptoms. What he does say is harrowing.

Some photos of him can be found at http://www.google.com/search?q=W.+N.+P.+Barbellion+photos&hl=en&rls=com.microsoft:en-us:IE-SearchBox&rlz=1I7GGLL_en&prmd=ivnso&tbm=isch&tbo=u&source=univ&sa=X&ei=gpCmTernNYGdgQez4In0BQ&ved=0CBcQsAQ&biw=775&bih=307

3 August 2004

UPDATED 7 July 2009:

Someone who commented here has called my attention to two Websites where this book is available for Internet reading:

http://www.archive.org/details/journalofdisappo00barbuoft

and

http://www.pseudopodium.org/barbellionblog

Many thanks to Katja!

_________________________________

CUSK, RACHEL

OUTLINE (2014)

This novel is the first part of a trilogy, but I don't feel prompted to continue with the other parts. Here we have a narrator but we don't find out much about her (only an outline is given). She's in Greece to teach a writing course. Each of the chapters focuses on various people who are in her life at the time--though none of these people is especially close to her, seemingly.

If anything happens in this novel, it is the narrator's somewhat surprising willingness to join an older man who sat beside her on the plane on his boat--just the two of them, and of course the situation turns into one where she fends him off.

Towards the end, her last encounter is with another writing teacher who turns up--Ann, who tells about her experience, mentioning that she has always seemed to be merely an outline while other people's lives were the subject of attention and interest.

This is what has been going on all along in this attempt at a story. which often resembles a series of journal entries made by someone traveling in Greece who later decided to string them together into a "story" with herself at the center, except that there is so little of herself showing up in the story that we become aware of how very anonymous and amorphous she is--which is her point, it seems.

Maybe she is trying to say something about many women and the way we are, whether by nature or upbringing.

But the narrative has some subtle, telling touches. Being alone on a boat with a man who is little more than an acquaintance, the narrator puts herself at risk, and this becomes apparent--to the reader at least and probably to her--when she is declining his overtures while he--in charge of the boat--is playing with a knife he's been using to cut a rope. His superior strength and her vulnerability come through to us loud and clear in that small scene.

By the end of the novel, the narrator has made arrangements to go sightseeing with her new friend Ann just before departing--and she turns down an offer from "my neighbor" (her phrase for the man met on the plane) of another boat ride. It looks as if she's learned something.

All in all, this was a slight and disappointing story.

May 8, 2018

TRANSIT (2017)

More vignettes make up this second volume in Rachel Cusk's trilogy. Not much happens by way of a plot. The narrator, whose name is Faye (we find out when it is used just once), is having work done on her house and is troubled by a downstairs neighbor who keeps banging on the ceiling.

Towards the end there are some children--including (over the phone) the narrator's two boys.

That's about it for this book. There are some attempts at profundity, as when the narrator's cousin declares somewhat obscurely: "Fate is only truth in its natural state" or when a hairdresser says, "To stay free, you have to reject change."

It's almost as if Cusk wrote up some incidents, strung them together in chapter form, threw in a few statements using more abstract words and hoped it would pass as a novel because putting together a real story, with a plot involving interactions among the characters, was simply beyond her.

9 April 2021

2 comments:

FYI - there are several online versions of this book:

http://www.archive.org/details/journalofdisappo00barbuoft

http://www.pseudopodium.org/barbellionblog/

Hi Katja--Thanks so much for adding the information on the online versions!--wordswordswords AKA agate

Post a Comment